This week I have written about Richard James Potter Clarke – the only son of James Clarke. If you have anything to add – or any corrections- please let me know!

This week I have written about Richard James Potter Clarke – the only son of James Clarke. If you have anything to add – or any corrections- please let me know!

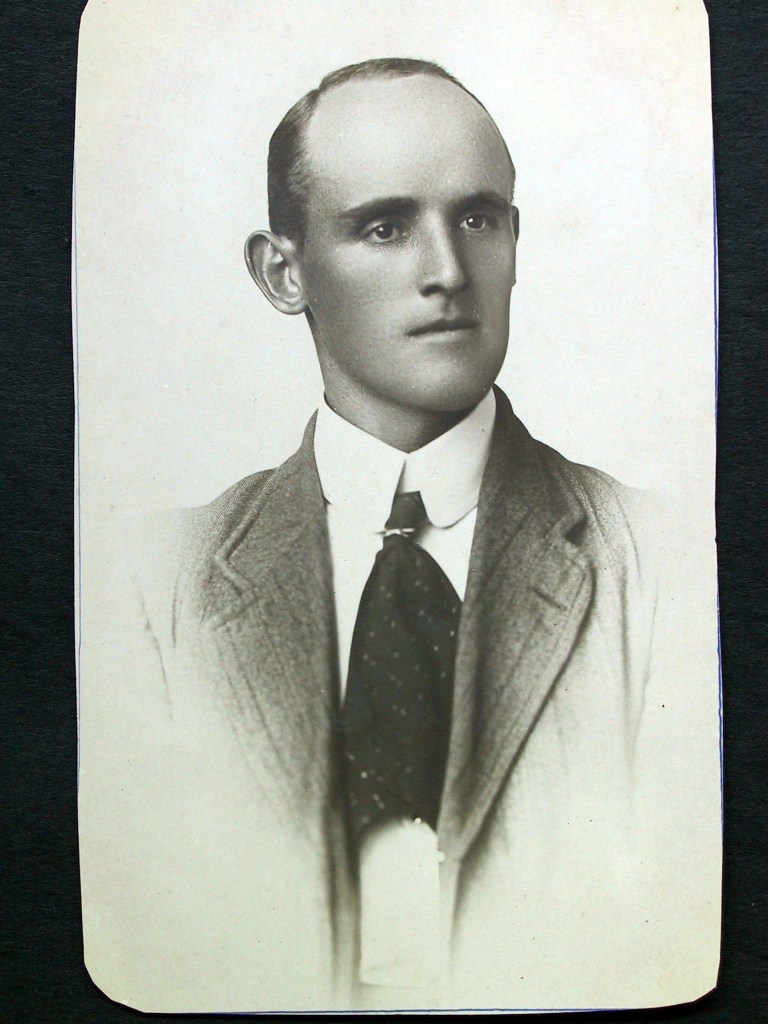

Richard James Potter Clarke Was the only son of James Clarke and Mary Potter – and I think his name reflects the hopes they had for him. As well as carrying both their surnames forward, Richard and James are also names frequently found in the Clarke and Potter histories.

I’m not sure what Richard Clarke did before he emigrated with his family to Western Australia in 1910. I presume he helped his father with his farming interests. In 1910 Richard Clarke came to WA on a different ship with the family’s prize Shire horses. Richard went to Albany where he had to stay with the horses for the six months they were in quarantine.

From 1916 to 1921 Richard can be found in the Electoral Rolls where his address is Avon Shed Farm, “Long Lawford”, Kumminin, Western Australia. Seems they tried to transplant a bit of England in the Australian wheatbelt! Richard lists his occupation as a farmer, and I presume was managing his father’s farm in Kumminin (his father James died in 1916). After that Richard disappears from the electoral Rolls until 1931 when he is listed as living with his wife Maggie in South Perth and his occupation as a Land Salesman. I’m not sure why he left farming… I guess we will never know.

Richard married Maggie Brown in 1918 and they had three children. Maggie sued for divorce on the grounds of desertion in 1935. The Daily News Newspaper quotes her as saying” Her husband had been a land agent in Perth, but in 1931 his income was so small that he accepted a position in Singapore. ‘He went there with her consent and remitted to her £5 a ‘week. He left without saying good-bye.

Later on, he wrote to her and intimated that he would never return to live with her. He said that he had gone away because he was in love with another woman. She asked him to come back to her for the sake of their children, but he refused. ‘ A decree nisi was granted on the grounds of desertion. Shortly after the divorce he married Anne Moffat in Singapore. They had three children.

Richard Clarke’s efforts to run a business in Singapore mainly resulted in failure. He first set up business in 1933 and called it the West Australian Sheep Supply and had a farm at the 101/2 mile, Changi Road where he pastured his sheep. He had a great deal of difficulty with the sheep, so he turned to pigs instead. However, that failed as well. He filed for bankruptcy in 1939. After reading the long article about his various ventures in the Bankruptcy Court (published in The Straits Times) I am unsure whether he was a victim of the different climate and cultures, was an unlucky entrepreneur or loveable rogue that was always in the lookout for some business proposition.

In 1941 Richard was caught up in the terrible events of the Second World War. Richard and his wife and children were still living in Singapore when it became apparent that they were in imminent danger of being over-run by the Japanese.

There is an excellent website that tells the story of the Singapore Civilian detainees. This website documents what happened to a group of civilian internees captured and held by the Japanese starting in February-March 1942 and ending in November 1945. The information I have here is from this website – and the text on this website are based on the work of Judy Balcombe. http://muntokpeacemuseum.org/ The Palembang and Muntok Internees of WW2

The story begins when the Japanese army invaded Malaya on December 8th, 1941. It was a planned and coordinated assault on the world. On that day, as the hours passed, Pearl Harbour in Hawaii, Manila, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaya were bombed and the inappropriately named ‘Pacific’ War began. It was to last for nearly 4 years; hundreds of thousands died or were taken prisoner and for the survivors, life was altered forever.

Men under 50 living in Singapore and Malaya were required to continue in their jobs, providing tin and rubber for the European War and maintaining infrastructure. They were required to join the fighting forces of the Malayan and Singapore Volunteers. They were not permitted to leave Singapore or Malaya without a permit.

It is said that 44 ships carrying evacuees left Singapore on those last days between February 12 to 14, 1942 and that of these vessels, all but 4 were bombed and sunk as they passed down the Bangka Straits from Singapore to Java. We do know his wife Anne and his children arrived in Fremantle on the 23 Jan 1942 – only about 3 weeks before Singapore fell to the Japanese. Considering that many ships that were evacuating civilians were sunk by the Japanese in the last few weeks they are probably lucky they made it to Fremantle at all.

Accurate records were not kept in the chaos of boarding and no one knows with certainty how many passengers there were, but it is thought that between 4 and 5 thousand people lost their lives as the ships went down.

Richard was taken prisoner by the Japanese when Singapore fell and then endured a couple of years of terrible deprivation as a civilian internee.

Muntok was used by the Japanese over two time periods: first for about a month from mid-February to mid-March 1942. And second from 19 September 1943 to March 1945 – one year and six months – during which 270 of the 960 internees met their deaths. Before that, between March 1942 and September 1943 the internees were held at Palembang.

One hundred and two British and Australian internees (sixty-two men and forty women) died at Muntok between October 1943 and March 1945. In the same period over three hundred Dutch men died.

For the most part, the British and Australians civilians were not moved, and their graves remained at Muntok. Their respective governments said that they had no duty of care for civilian dead. As a result, the graves of those who were left behind began to deteriorate and the wooden crosses which bore their names and dates of death started to rot away. As a result of this lack of preservation the vast majority of the civilian internees had no named or identifiable grave and soon the local population began to build over the graveyard.

A list was maintained, perhaps by William McDougall, of the deaths of each male internee, the date of death, and cause of death. Although the conditions were harsh, meticulous records were kept of where each individual was buried and as a result we have plans of the grave site which have allowed us to reconstruct approximately where many of the Australian, British, and other Commonwealth civilians were buried.

Richard James Potter Clarke’s gravesite is known, and he is at location F10 in the burial ground. On a handwritten list of the deaths Richard Clarke is listed as dying on the 23 November 1944 whereas many official records state the 19 November 1944. He died of Malaria and Dysentery.

So, Richard James Potter Clarke, son of an English Yeoman, born into some privilege lived a different life than perhaps he could have done. For whatever reason he chose not to continue with his father’s farm and tried to try and make his fortune in different areas. Unfortunately, world events engulfed him, and he died a terrible death away from all his family and friends.

Link to Internees website

Link to Newspaper articles

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/…/straitstimes19390722-1…

Leave a comment